I remember my years at The University of Vermont (UVM) in the early 2000s as days of idealism—passionate people driven with passionate resolve to change the world around them.

People who created alternative fuel vehicles to travel across the country, devoted themselves to sustainable organic farming, pushed boundaries through international travel, created music, made art, started businesses that prioritized people over profits.

These were types of people I hadn’t met before; people who saw the world through the prism of kindness, happiness, and justice rather than salaries, rankings or reputations. These were people who saw the world as ripe for change. And I couldn’t help but learn from these people and take this higher calling with me on my journey.

Fifteen years later, I have devoted myself to a philosophy of hyper-local activism; of the ripples I can make in my little corner of the world than can resonate outward.

It started when I taught high school in West Philadelphia.

We invited our seniors and their families into school for what we called "Financial Fit" meetings—conferences wherein students would use spreadsheets to input their scholarships, grants, and loans offered from all the colleges and universities to which they had been accepted. Families would be able to see—in real-time—what their out-of-pocket costs would be, what their debt load would be after graduation and what their monthly loan payments would be.

It was then [pullquote]I saw the way our baked-in systems of inequity have constructed an educational system wherein it is better to be rich and privileged than hard-working.[/pullquote]

These students did everything asked of them. They came to school, did the work, out-performed their peers, took extra-curriculars, earned internships—but at the end of the day, what really mattered was their “Expected Family Contribution” (EFC) on their FAFSA; the amount of money their families would have to come up with—out of pocket—to attend college.

For the vast majority of our students, these costs, even after generous scholarships, loan packages, and Pell grants, made attending a four-year college or university simply unrealistic.

And they cried. The students cried because, [pullquote position="right"]once again, they ran up against a system that wasn’t made for them.[/pullquote] The families cried because, once again, they ran up against a system that wasn’t made for them.

And I thought back to my teenage self—a privileged white kid who never for a moment wondered how college was going to be paid for; a privilege I did not earn but was afforded nonetheless.

But in the face of such large injustice, what could be done? How could one 12th grade English teacher make an impact?

It started, as so many things do nowadays, with an email.

Could I take some students from West Philadelphia up to visit UVM? The answer was yes. And soon, every year, 10 students from West Philadelphia were participating in an overnight program called Discovering UVM.

But there were students from other schools who also wanted to go. Would it be OK if we extended this relationship to our sister-schools? The answer was yes, and then, students from a network of seven high schools in Philadelphia and Camden were participating in Discovering UVM.

But actually attending UVM was still financially out of reach for most of these students.

Could anything be done?

The answer was yes. And with that, in 2014, the UVM Affinity Program with Mastery Schools was born—a relationship in which up to five Mastery students, every year, are offered nearly full-ride scholarship packages.

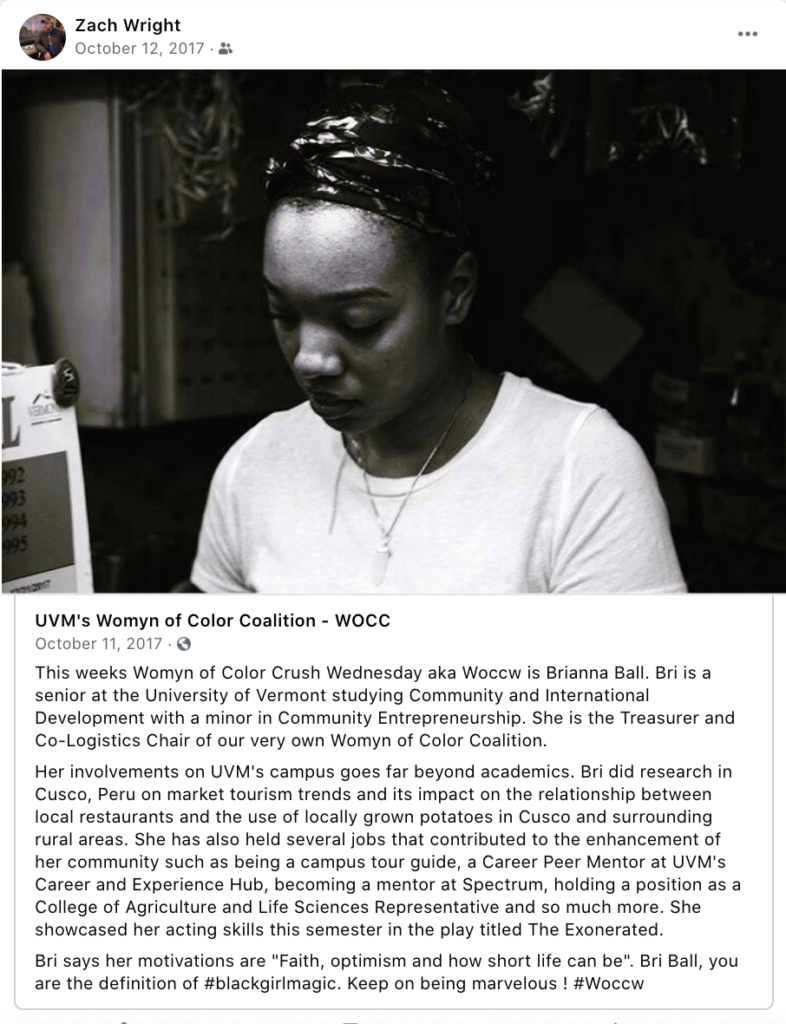

The first graduate Was Brianna Ball, class of 2019.

This year, the class of 2020 will see three graduates, two of whom I taught in their 12th grade year: Phylicia Hodges, Kelayah Gregg and RiRi Stuart-Thompson. Many more are Juniors, Sophomores and first years.

It’s a small ripple. The tiniest of pebbles thrown into the pool of systematic injustice.

And there are more stones to throw.

So often, those who work for justice and equity look outwards. We look to other communities to serve, overlooking the very injustices that exist in our own neighborhoods.

So I started to look a bit closer to home for my next stone, and it didn’t take long to find.

It is no secret that disciplinary disparities in suspension rates exist along lines of race, wealth, and ability. Under the Obama administration, the Department of Education created databases with which civil rights abuses could be identified and addressed.

While such databases have since ceased tracking data since Trump came into office, the databases are still accessible to any with an internet connection.

The trends are striking. According to the findings,

Black children represent 18% of preschool enrollment, but 48% of preschool children receiving more than one out-of-school suspension … Black students are expelled at a rate three times greater than white students … Students with disabilities are more than twice as likely to receive a suspension that a student without disabilities … Students with disabilities represent 12% of the student population, but 58% of those placed in seclusion or involuntary confinement and 75% of those physically restrained at school.

It’s enough to make you weep and sink into paralyzed apathy.

After all, the injustices are so great, the issues so large, what can one person do?

What ripples can one stone make in a sea so vast?

This is where commitment to hyper-local activism comes in.

I know I cannot change our nation with its history of systemic injustice. But what about my small New Jersey town?

I started digging into the data. It turns out that our town, a lovely progressive space outside of Philadelphia with a thriving cultural center, has disciplinary disparities greater than the New Jersey as well as national averages.

Whereas a White student has a roughly 4% chance of getting suspended from the local high school, a Black student has a 10%, a Latinx student has an 8% chance and a student with a disability has a 20% chance.

This isn’t about casting blame, pointing fingers or accusation. [pullquote]We are Americans, and thus inevitably wrapped up in the implicit biases and predispositions that come with being raised in this nation.[/pullquote]

It’s about our babies; all of our babies. It’s about living up to the morality of our words.

So we are taking action, convening meetings to identify disparities to attack, listening to students and families to get their perspectives, listening to educators to get their perspectives, calling on local and state-level advocacy groups—and then mobilizing our local board of education to implement tangible, measurable and immediate change.

It’s another small stone, a tiny ripple in the sea.

But I think back on those passionate people who taught me so much, and I think of the ripples we can all make, the pebbles we can all throw. And I begin to see the tidal wave of change that is coming.

Zachary Wright is an assistant professor of practice at Relay Graduate School of Education, serving Philadelphia and Camden, and a communications activist at Education Post. Prior, he was the twelfth-grade world literature and Advanced Placement literature teacher at Mastery Charter School's Shoemaker Campus, where he taught students for eight years—including the school's first eight graduating classes. Wright was a national finalist for the 2018 U.S. Department of Education's School Ambassador Fellowship, and he was named Philadelphia's Outstanding Teacher of the Year in 2013. During his more than 10 years in Philadelphia classrooms, Wright created a relationship between Philadelphia's Mastery Schools and the University of Vermont that led to the granting of near-full-ride college scholarships for underrepresented students. And he participated in the fight for equitable education funding by testifying before Philadelphia's Board of Education and in the Pennsylvania State Capitol rotunda. Wright has been recruited by Facebook and Edutopia to speak on digital education. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, he organized demonstrations to close the digital divide. His writing has been published by The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Philadelphia Citizen, Chalkbeat, Education Leadership, and numerous education blogs. Wright lives in Collingswood, New Jersey, with his wife and two sons. Read more about Wright's work and pick up a copy of his new book, " Dismantling A Broken System; Actions to Close the Equity, Justice, and Opportunity Gaps in American Education"—now available for pre-order!

If you have a child with disabilities, you’re not alone: According to the latest data, over 7 million American schoolchildren — 14% of all students ages 3-21 — are classified as eligible for special...

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

The story you tell yourself about your own math ability tends to become true. This isn’t some Oprah aphorism about attracting what you want from the universe. Well, I guess it kind of is, but...

Your donations support the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.