When Michelle Obama and her husband visited students of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation in North Dakota in the summer of 2014, she met students whose lives had been ravaged by substance abuse and alcoholism. In a high school class of 70, four or five students had committed suicide. Though last month was Native American Heritage Month, that fact mostly flew under the radar. Overall, it was one of many missed opportunities to acknowledge the urgent hardships faced by our country’s first citizens, and more specifically, their children.

While the Every Student Succeeds Act, passed in 2015, was a huge boon for Indian education, increasing opportunities for indigenous communities to control their education systems,

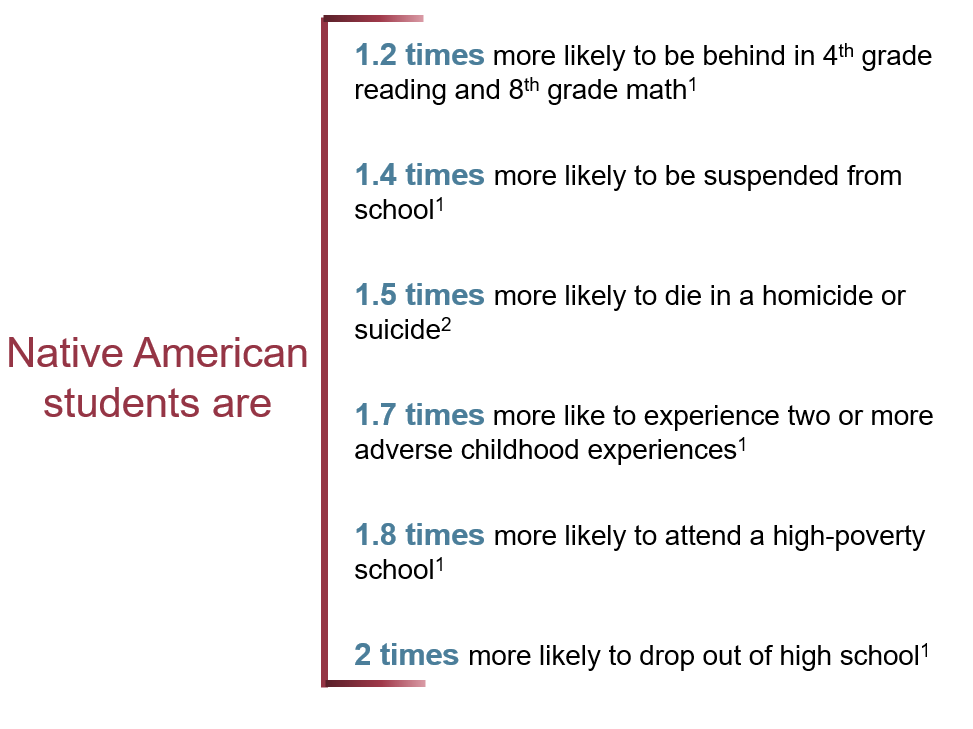

Native students around the country still languish in failing schools and often face worse outcomes than their White, Black and Latino peers.

How, exactly, did we get here? America has never been good to its Native people. When genocide, forced removal, and overt efforts at cultural assimilation fell out of favor in the 1950s, the government turned to another tactic to destroy Native American culture: relocation. In short, this practice enticed and sometimes coerced families to leave their homes on reservations and set out into the urban unknown. Promised jobs, housing, and better education options for both parents and children, many Native Americans quickly realized that the government’s description of urban life was unreasonably optimistic.

For too many, relocation was a bust. Native families were stranded in cities, far from home, isolated from their languages and cultures. The aftermath of relocation was hardest on Native children. Relocation systematically disrupted the cultures and communities children had known their entire lives. In public schools, they had to navigate the politics of language, racial segregation, and discrimination without the guidance of their elders or the camaraderie of their Native peers.

In 1969, a Senate report concluded that the “coercive assimilation” Native children faced at school had turned the classroom into a “battleground.” This contentious environment ultimately resulted in poor school attendance, high dropout rates, low self-esteem, academic failure, and a “perpetuation of the cycle of poverty.” Today, Native children still face a suite of obstacles unparalleled in American schools. They often attend chronically underfunded schools, both on and off reservations, and they rarely have access to culturally relevant curriculum or culturally competent educators. When compared to the average outcomes for all students, the challenges Native American students face are horrifying:

Many researchers link the root of these challenges to historical trauma. For hundreds of years, the Native experience has been undermined by the terror and shame inflicted upon it by America and her citizens. Research indicates that that terror and shame has rippled throughout generations of children, displaying itself in the poverty, poor physical and mental health, and subpar education outcomes that wreak havoc on Indian country today. No one knows the dire circumstances that mar the lives of Native youth better than Native youth themselves. Sam Schimmel, an Alaska Native teenager, explains the importance and urgency of culture-based education:

I see that, among my peers, I am much less likely to fall prey to alcoholism and much less likely to be suicidal as a result of being brought up in the laps of my elders, listening to stories and being engaged on a cultural level. What I've seen is that when youth are not culturally engaged, you see higher rates of incarceration, higher rates of suicide, higher rates of alcoholism, higher rates of drug abuse—all these evils that come in and take the place of culture.

In spite of those dire circumstances, there are solutions to these problems, and they often lie within Native communities, in the hearts and mind of Native people. For example, there is growing evidence that culture-based education is positively correlated with students’ socio-emotional well-being and academic achievement.

The National Indian Education Association (NIEA), a current client of Bellwether Education Partners, was founded in 1970 and works to advance culture-based education opportunities for American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians. By convening and training educators, promoting cultural and language education, and building relationships with policymakers, NIEA champions the idea that centering learning around culture is the key to success for Native students. Thanks in large part to NIEA’s advocacy, the Every Student Succeeds Act, passed just three years ago, bolstered Native education in key ways:

While their history has been scarred by efforts to annihilate culture and force assimilation, indigenous culture is full of rich, beautiful traditions, economic and social contributions, and deep and inspiring creativity and resilience. For too long, the education system has served as a weapon against Native Americans. It’s time that it becomes a tool for righting (and learning from) our nation’s wrongs.

Katrina Boone is an associate partner with Bellwether Education Partners in the Policy and Evaluation practice area, focusing on issues related to evaluation and planning, evaluation capacity building, and data analysis. Currently, Katrina supports several education organizations as they seek to better tell the stories of their impact. Beyond evaluation, Katrina’s interests include teacher pipelines and diversity, the history of education in America (particularly as it applies to communities furthest from opportunity), and the intersection of science, poverty, and education. Prior to joining Bellwether in 2018, Katrina worked as the Director of Teacher Outreach at the Collaborative for Student Success, a national nonprofit working to improve public education through a commitment to high standards for all students. There she spearheaded a process for building the capacity of the organization and its teacher fellows for evaluation and continuous improvement. She also worked as a Teacher Leader on Special Assignment at the Kentucky Department of Education, engaging teachers in conversations about education policy and supporting schools as they designed and implemented teacher leadership plans. Katrina began her career by spending eight wonderful years as a high school English teacher in Kentucky, where she taught in urban, rural, and suburban schools. She holds a Master of Arts in Teaching degree from Morehead State University and a bachelor’s degree from the University of Kentucky.

If you have a child with disabilities, you’re not alone: According to the latest data, over 7 million American schoolchildren — 14% of all students ages 3-21 — are classified as eligible for special...

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy...

The story you tell yourself about your own math ability tends to become true. This isn’t some Oprah aphorism about attracting what you want from the universe. Well, I guess it kind of is, but...

Your donations support the voices who challenge decision makers to provide the learning opportunities all children need to thrive.

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020–2024 brightbeam. All rights reserved.